BORKEN, Germany — The European Union’s dream of using vegetable-based diesel fuel in cars to cut oil imports and the pollution that causes global warming is turning sour.

The bloc made a big bet on biodiesel fuels in 2003, agreeing that its governments would phase in tax breaks and rules to encourage their production and use.

The bet seemed to make sense. Most Europeans drive diesel cars, making ethanol — the U.S. clean fuel of choice for gasoline-powered cars — impractical. Biodiesel can be mixed with regular diesel fuel and, when blended, doesn’t need any special pumps or engine-design changes.

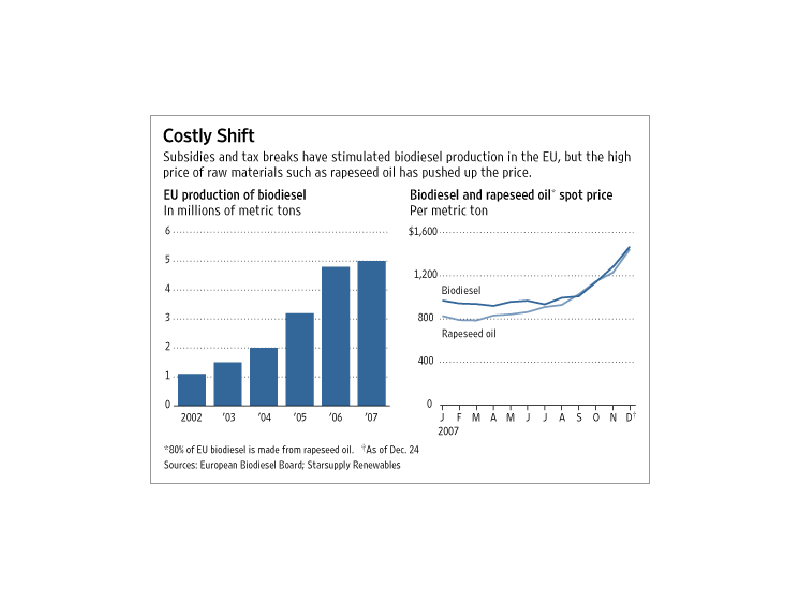

Mirroring the U.S. experience with ethanol, European companies rushed to make biodiesel out of a range of things, including rapeseed crops and used McDonald’s frying oil. Low raw-material costs and generous tax breaks meant margins were high. By last year, Europe’s annual capacity to make the fuel had climbed to 10 million metric tons from two million tons in 2003.

As with ethanol in the U.S., though, Europe now has a glut of biodiesel. The world consumed only nine million tons of biodiesel last year. Europe’s producers found buyers for just five million tons. The industry is in trouble, under pressure from soaring costs, disappearing tax breaks, less-costly imports and waning public support.

The trend is at odds with the conventional wisdom that rising oil prices make green energy more attractive. It also means the EU risks missing the goal it set in 2003 of replacing 10% of transportation fuel with nonfossil fuels by 2020.

The 27-nation bloc, which claims to lead the world in cutting the carbon-dioxide emissions believed to cause global warming, uses nonfossil fuels for less than 2% of transportation fuel consumed.

Since January, prices for the crops that make most biodiesel have doubled, driving the cost of a ton of biodiesel up 50%, to around $1,440 a ton, or about $4.80 a gallon. Prices for regular crude-oil-based diesel have risen sharply, too, but only to $840 a ton, or $2.80 a gallon. Biodiesel has become more expensive for oil companies to buy than fossil fuel, and they are cutting back.

Green lobbies are also turning against biodiesel. They now say that growing crops for biodiesel puts too much pressure on land and food prices. In Europe, 80% of biodiesel is made from rapeseed, a distinctive, yellow-flowered crop. Environmental groups also oppose imported palm-oil-based biodiesel from countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia, saying the rush to grow more oil palm trees is causing deforestation.

The combination of problems has hit producers hard. Petrotec AG, based here in Borken, Germany, makes biodiesel out of used cooking oil from McDonald’s, Burger King and other restaurants. After going public last year, its market capitalization quickly climbed to & euro;200 million ($288 million). But when the German government cancelled a biodiesel tax credit in August 2006, Petrotec’s share price halved, and the company shed workers.

“How are we meant to invent and develop new technology if we can’t make money?” asks Petrotec Chief Executive Roger Boeing, who started the firm in 1998. He helped pioneer a technology for converting recycled oil into biodiesel, but it still isn’t efficient enough to make biodiesel less expensive than normal diesel.

A prominent British company, Biofuels Corp., avoided a bankruptcy situation this year after Barclays Bank agreed to swap some of its debt outstanding for 94% of the equity in the company. The company blamed high commodity prices and biodiesel imports from the U.S. for its woes.

U.S. biodiesel producers enjoy a big tax credit from the federal government. This month, Congress voted to extend the tax credit until the end of 2010. EU producers recently asked the EU to impose punitive tariffs on biodiesel imports from the U.S., citing the subsidies as unfair competition. U.S. producers dispute the claim.

“We’re still working on a big technological breakthrough to bring costs down,” says Bruno Reyntjens, a manager at Proviron, a Belgian company that makes biodiesel out of rapeseed and soybeans.

Scientists say it is likely to be at least 2010 before any breakthrough is made on costs, or on producing a biodiesel than can run in regular diesel engines effectively at a much higher blend than the current standard of 5% per gallon of diesel sold at the pump.

Europe’s governments are finding it difficult to adjust policy to a new and volatile market. In 2006, when commodity prices were low and margins were fat, Germany decided to trim the tax breaks it offers to biodiesel producers. Earlier this year, France raised taxes on biodiesel. Now that producers are in trouble, governments aren’t giving the tax breaks back.

“It’s public finances versus agriculture, and governments need money,” says Kevin McGeeney, chief executive of Switzerland-based Starsupply Renewables SA, a biofuels broker. Ten EU countries, including the United Kingdom, have delayed measures to force oil companies to blend biodiesel with their regular fuel.

The Paris-based International Energy Agency has urged EU governments to cut back further on incentives to develop biofuels, saying they are too expensive.

Peter Mandelson, the EU’s top trade negotiator, says the problem isn’t the use of biodiesel, but producing it in crowded, high-cost Europe. “Europe should be open to accepting that we will import a large part of our biofuel resources,” Mr Mandelson said in a speech this summer.

U.S. ethanol producers are facing some similar problems. Buoyed by $7 billion a year in subsidies and a tariff on foreign imports, U.S. farmers planted a quarter more corn this year, most of it going toward making ethanol. But supply of ethanol is outstripping demand, mainly because of the difficulty and cost of transporting ethanol, which needs special pipelines. Some U.S. ethanol producers are idling production and a debate has begun over whether the pressure that ethanol production puts on agricultural land is worth the modest cuts in carbon-dioxide emissions it yields.

To contact the reporter of this story:

John W. Miller at john.miller@dowjones.com